what factors led to the rise of the american indian movement in the 1960s?

| Chicano Motility | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Chicanismo | |||

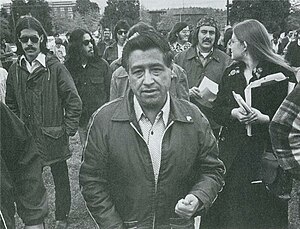

Cesar Chavez with demonstrators | |||

| Appointment | 1940s to 1970s - present | ||

| Location | Western U.s., Southwestern The states, Midwestern United States | ||

| Caused by | Racism in the United States, Zoot Accommodate Riots | ||

| Goals | Civil and political rights, Overthrow of the US government | ||

| Methods | Boycotts, Direct activeness, Draft evasion, Occupations, Protests, School walkouts | ||

| Status | (continued activism by Chicano groups) | ||

| Parties to the civil conflict | |||

| |||

| Lead figures | |||

| |||

The Chicano Movement, also referred to as El Movimiento, was a social and political movement in the U.s.a. inspired past prior acts of resistance amidst people of Mexican descent, particularly of Pachucos in the 1940s and 1950s,[i] [2] [3] [4] and the Black Ability movement,[5] [6] that worked to embrace a Chicano/a identity and worldview that combated structural racism, encouraged cultural revitalization, and accomplished community empowerment by rejecting assimilation.[vii] [8] Before this, Chicano/a had been a term of derision, adopted by some Pachucos as an expression of defiance to Anglo-American society.[nine] With the ascent of Chicanismo, Chicano/a became a reclaimed term in the 1960s and 1970s, used to express political autonomy, indigenous and cultural solidarity, and pride in being of Ethnic descent, diverging from the assimilationist Mexican-American identity.[10] [eleven] [12] Chicanos likewise expressed solidarity and defined their culture through the development of Chicano art during El Movimiento, and stood business firm in preserving their religion.[xiii]

The Chicano Motility was influenced by and entwined with the Black Ability motility, and both movements held similar objectives of community empowerment and liberation while likewise calling for Black-Dark-brown unity.[5] [6] Leaders such as César Chávez, Reies Tijerina, and Rodolfo Gonzales learned strategies of resistance and worked with leaders of the Blackness Power motion. Chicano organizations like the Chocolate-brown Berets and Mexican American Youth Arrangement (MAYO) were influenced past the political agenda of Black activist organizations such equally the Black Panthers. Chicano political demonstrations, such every bit the East L.A. Walkouts and the Chicano Moratorium, occurred in collaboration with Black students and activists.[five] [8]

Similar to the Blackness Power motility, the Chicano Movement experienced heavy state surveillance, infiltration, and repression from U.S. authorities informants and amanuensis provocateurs through organized activities such as COINTELPRO. Motion leaders similar Rosalio Muñoz were ousted from their positions of leadership past government agents, organizations such as MAYO and the Brown Berets were infiltrated, and political demonstrations such as the Chicano Moratorium became sites of police brutality, which led to the decline of the motility by the mid-1970s.[14] [15] [16] [17] Other reasons for the motion's refuse[ co-ordinate to whom? ] include its centering of the masculine subject, which marginalized and excluded Chicanas,[18] [19] [20] and a growing disinterest in Chicano nationalist constructs such every bit Aztlán.[21]

Origins [edit]

The Chicano Movement encompassed a broad list of issues—from restoration of land grants, to farm workers' rights, to enhanced education, to voting and political indigenous stereotypes of Mexicans in mass media and the American consciousness. In an article in The Journal of American History, Edward J. Escobar describes some of the negativity of the time:

The disharmonize between Chicanos and the LAPD thus helped Mexican Americans develop a new political consciousness that included a greater sense of ethnic solidarity, an acknowledgment of their subordinated condition in American guild, and a greater determination to act politically, and perchance fifty-fifty violently, to cease that subordination. While near people of Mexican descent notwithstanding refused to call themselves Chicanos, many had come to adopt many of the principles intrinsic in the concept of chicanismo.[22]

Early in the twentieth century, Mexican Americans formed organizations to protect themselves from discrimination. I of those organizations, the League of United Latin American Citizens, was formed in 1929 and remains active today.[23] The move gained momentum after Earth War II when groups such as the American M.I. Forum (AGIF), which was founded by returning Mexican American veteran Dr. Hector P. Garcia, joined in the efforts by other civil rights organizations.[24] The AGIF first received national exposure when it took on the crusade of Felix Longoria, a Mexican American serviceman who was denied a funeral service in his hometown of 3 Rivers, Texas later on being killed during WWII.[25] After the Longoria incident, the AGIF quickly expanded throughout Texas, and past the 1950s, capacity were founded across the U.Southward.[26]

Mexican American civil rights activists besides achieved several major legal victories including the 1947 Mendez 5. Westminster court example ruling which declared that segregating children of "Mexican and Latin descent" was unconstitutional and the 1954 Hernandez five. Texas ruling which alleged that Mexican Americans and other historically-subordinated groups in the United States were entitled to equal protection under the 14th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution.[27] [28]

Throughout the state, the Chicano Motion was defined by several unlike leaders. In New Mexico, at that place was Reies López Tijerina who worked on the state grant movement. He fought to regain control of what he considered ancestral lands. He became involved in civil rights causes inside six years and too became a cosponsor of the Poor People'due south March on Washington in 1967. In Texas, state of war veteran Dr. Hector P. Garcia founded the American GI Forum and was later appointed to the United States Commission on Civil Rights. In Denver, Rodolfo "Corky" Gonzáles helped ascertain the meaning of being a Chicano through his poem Yo Soy Joaquin (I am Joaquin)[one]. In California, César Chávez and the subcontract workers turned to the struggle of urban youth, and created political awareness and participated in La Raza Unida Party.

The most prominent ceremonious rights arrangement in the Mexican-American community is the Mexican American Legal Defence force and Educational Fund (MALDEF), founded in 1968.[29] Although modeled after the NAACP Legal Defence and Educational Fund, MALDEF has too taken on many of the functions of other organizations, including political advocacy and training of local leaders.

Some women who worked for the Chicano movement felt that members were being too concerned with social problems that affected the Chicano community, instead of addressing problems that affected Chicana women specifically. This led Chicana women to class the Comisión Femenil Mexicana Nacional. In 1975, it became involved in the example Madrigal v. Quilligan, obtaining a moratorium on the compulsory sterilization of women and adoption of bilingual consent forms. These steps were necessary considering many Latina women who did not sympathise English language well were being sterilized in the United States at the fourth dimension, without proper consent.[30] [31]

While the widespread immigration marches flourished throughout the U.S. in the Spring of 2006, the Chicano Movement connected to expand in its focus and its active participants. Every bit of the 21st Century, a major focus of the Chicano Movement has been to increment the (intelligent) representation of Chicanos in mainstream American media and entertainment. There are also many customs education projects to educate Latinos about their voice and power like South Texas Voter Registration Project. SVREP's mission is to empower Latinos and other minorities by increasing their participation in the American democratic process. Members of the outset of the Chicano movement, like Faustino Erebia Jr., still speak almost their trials and the changes they have seen over the years.[32] [33]

The motility started small in Colorado nevertheless spread beyond the states condign a worldwide motion for equality. While there are many poets who helped bear out the motion, Corky Gonzales was able to spread the Chicano issues worldwide through "The Plan Espiritual de Aztlán." This manifesto advocated Chicano nationalism and self-determination for Mexican Americans. In March 1969 it was adopted by the Starting time National Chicano Liberation Youth Conference based in Colorado. Adolfo Ortega says, "In its core as well as its fringes, the Chicano Motility verged on strivings for economic, social, and political equality." This was a simple message that any ordinary person could relate to and want to strive for in their daily lives. Whether someone was talented or not they wanted to assist spread the political bulletin in their own way. While bulk of the group consisted of Mexican-Americans many people of other nationalities wanted to help the motion. This helped moved the motion from the fringes into the more than mainstream political establishment. The "Political Establishment" typically consisted of the dominant grouping or elite that holds power or say-so in a nation. Many successful organizations were formed, such every bit the Mexican American Youth Organization, to fight for civil rights of Mexican Americans. During the early 1960s in Texas many Mexican-Americans were treated like second class citizens and discriminated against. While progress has been made for equality immigrants even to this day are still a target of misunderstanding and fearfulness. Chicano Poetry was a safe manner for political letters to spread without fright of being targeted for by speaking out. Politically, the motility was as well broken off into sections like chicanismo. "Chicanismo meant to some Chicanos dignity, self respect, pride, uniqueness, and a feeling of a cultural rebirth." Mexican-Americans wanted to embrace the colour of their skin instead of information technology being something to be aback of. Many Mexican-Americans unfortunately had it ingrained on them through club that it was meliorate socially and economically to act "White" or "Normal." The movement wanted to interruption that mindset and comprehend who they were and be loud and proud of it. A lot of people in the movement thought it was adequate to speak Spanish to one another and non be ashamed of not being fluent in English. The move encouraged to not only discuss tradition with other Mexican-Americans but others not within the move. America was a land of immigrants not just for the social and economically accepted people. The motility made it a point not to exclude others of other cultures but to bring them into the fold to make everyone agreement of one another. While America was new for many people of Latin descent it was important to celebrate what made them who they were as a culture. Entertainment was powerful tool to spread their political message within and out of their social circles in America. Chicanismo might not be discussed frequently in the mainstream media merely the principal points of the move are: self-respect, pride, and cultural rebirth.

This is a list of the major epicenters of the Chicano Movement.

- Albuquerque

- Chicago

- Corpus Christi

- Dallas

- Delano

- Denver

- El Paso

- Fresno

- Houston

- Las Vegas

- Los Angeles

- Oakland

- Phoenix

- San Antonio

- San Diego

- San Jose

- Santa Barbara

- San Francisco

- Sacramento

Chicanas in the motility [edit]

The Brown Berets marching in 1970.

While Chicanas are typically not covered as heavily in literature about the Chicano movement, Chicana feminists accept begun to re-write the history of women in the motility. Chicanas who were actively involved within the movement have come to realize that their intersecting identities of existence both Chicanas and women were more complex than their male counterparts.[34] Through the involvement of various movements, the main goal of these Chicanas was to include their intersecting identities within these movements, specifically choosing to add women's issues, racial issues, and LGBTQ problems within movements that ignored such identities.[35] One of the biggest women's bug that the Chicanas faced was that Mexican men drew their masculinity from forcing traditional female roles on women and expecting women to bear as many children equally they could.[36]

Sociologist Teresa Cordova, when discussing Chicana feminism, has stated that Chicanas change the discourse of the Chicano motility that condone them, as well equally oppose the hegemonic feminism that neglects race and class.[35] Through the Chicano movement, Chicanas felt that the motility was not addressing sure bug that women faced nether a patriarchal society, specifically addressing material weather. Within the feminist discourse, Chicanas wanted to bring awareness to the forced sterilization many Mexican women faced during the 1970s.[35] The picture show No Mas Bebes describes the stories of many of these women who were sterilized without consent. Although Chicanas take contributed significantly to the move, Chicana feminists have been targeted; they are targeted because they are seen equally betraying the motility and being anti-family unit and anti-men.[35] Past creating a platform that was inclusive to various intersectional identities, Chicana theorists who identified every bit lesbian and heterosexual were in solidarity of both.[35] With their navigation through patriarchal structures, and their intersecting identities, Chicana feminists brought issues such as political economy, imperialism, and class identities to the forefront of the movement'south discourses. Enriqueta Longeaux and Vasquez discussed in the Third World Women'south Conference, "There is a need for world unity of all peoples suffering exploitation and colonial oppression here in the U.Southward., the most wealthy, powerful, expansionist country in the world, to identify ourselves as third globe peoples in social club to terminate this economical and political expansion."[37]

Geography [edit]

Scholars have paid some attention to the geography of the movement and situate the Southwest as the epicenter of the struggle. All the same, in examining the struggle'due south activism, maps permit us to see that activity was not spread evenly through the region and that certain organizations and types of activism were limited to particular geographies.[38] For instance, in southern Texas where Mexican Americans comprised a significant portion of the population and had a history of balloter participation, the Raza Unida Political party started in 1970 past Jose Angel Gutierrez hoped to win elections and mobilize the voting ability of Chicanos. RUP thus became the focus of considerable Chicano activism in Texas in the early 1970s.

The movement in California took a different shape, less concerned about elections. Chicanos in Los Angeles formed alliances with other oppressed people who identified with the Third World Left and were committed to toppling U.Due south. imperialism and fighting racism. The Brown Berets, with links to the Black Panther Political party, was one manifestation of the multiracial context in Los Angeles. The Chicano Moratorium antiwar protests of 1970 and 1971 also reflected the vibrant collaboration between African Americans, Japanese Americans, American Indians, and white antiwar activists that had developed in Southern California.

Chicano student activism too followed particular geographies. MEChA established in Santa Barbara, California, in 1969, united many university and college Mexican American groups under one umbrella organization. MEChA became a multi-state organization, but an exam of the year-by-twelvemonth expansion shows a continued concentration in California. The Mapping American Social Movements digital project shows maps and charts demonstrating that as the organization added dozens so hundreds of chapters, the vast majority were in California. This should cause scholars to ask what weather condition fabricated the country unique, and why Chicano students in other states were less interested in organizing MEChA chapters?

Political activism [edit]

Members of MEChA protesting for gratis college tuition at the Colegio César Chávez in Mt. Affections, Oregon.

In 1949 and 1950, the American G.I. Forum initiated local "pay your poll tax" drives to register Mexican American voters. Although they were unable to repeal the poll tax, their efforts did bring in new Latino voters who would begin to elect Latino representatives to the Texas House of Representatives and to Congress during the late 1950s and early 1960s.[39]

In California, a similar phenomenon took place. When World War II veteran Edward R. Roybal ran for a seat on the Los Angeles Metropolis Council, community activists established the Community Service Organization (CSO). The CSO was effective in registering xv,000 new voters in Latino neighborhoods. With this newfound support, Roybal was able to win the 1949 election race confronting the incumbent councilman and became the first Mexican American since 1886 to win a seat on the Los Angeles City Council.[40]

The Mexican American Political Association (MAPA), founded in Fresno, California, came into being in 1959 and drew upward a plan for directly electoral politics. MAPA soon became the primary political voice for the Mexican-American community of California.[41]

Student walkouts [edit]

After World War Two, Chicanos began to assert their own views of their own history and status equally Mexican Americans in the US and they began to critically clarify what they were being taught in public schools.[42] Many young people, like David Sanchez and Vickie Castro, founders of the Brown Berets, establish their voices in protesting the injustices they saw.[43]

In the tardily 1960s, when the student motion was active around the world, the Chicano Movement inspired its own organized protests like the East Fifty.A. walkouts in 1968, and the National Chicano Moratorium March in Los Angeles in 1970.[44] The student walkouts occurred in Denver and East LA in 1968. There were besides many incidents of walkouts outside of the city of Los Angeles, as far as Kingsville, Tx in South Texas, where many students were jailed by the county and protests ensued. In the LA Canton high schools of El Monte, Alhambra, and Covina (particularly Northview), the students marched to fight for their rights. Similar walkouts took place in 1978 in Houston loftier schools to protest the discrepant academic quality for Latino students. In that location were too several student sit-ins which objected the decreasing funding of Chicano courses.

The blowouts of the 1960s tin be compared to the 2006 walkouts, which were washed in opposition to the Illegal Immigration Control bill.

Pupil and youth organizations [edit]

Student protestation in support of the UFW boycott, San Jose, California.

Detail of the "Los Seis de Boulder" memorial sculpture on the University of Colorado Bedrock campus

Chicano student groups such every bit the United Mexican American Students (UMAS), the Mexican American Youth Association (MAYA) in California, and the Mexican American Youth Organisation in Texas, developed in universities and colleges in the mid-1960s. South Texas had a local chapter of MAYO that besides made significant changes to the racial tension in this surface area at the time. Members included Faustino Erebia Jr, local political leader and activist, who has been a keynote speaker at Texas A&M Academy at the annual Cesar Chavez walk.[45] [46] At the historic meeting at the University of California, Santa Barbara in Apr 1969, the diverse student organizations came together under the new proper name Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlán (MECHA). Between 1969 and 1971, MECHA grew rapidly in California with major centers of activism on campuses in southern California, and a few chapters were created along the East coast at Ivy League Schools.[47] Past 2012, MECHA had more than 500 capacity throughout the U.Due south. Student groups such equally these were initially concerned with education bug, merely their activities evolved to participation in political campaigns and to diverse forms of protestation confronting broader issues such as police brutality and the U.S. war in Southeast Asia.[46] The Brown Berets, a youth group which began in California, took on a more militant and nationalistic ideology.[48]

The UMAS movement garnered great attention in Boulder, Colorado after a car bombing killed several UMAS students.[49] In 1972, UMAS students at the University of Colorado Bedrock were protesting the university's mental attitude towards UMAS issues and demands.[49] Over the adjacent two years hostilities had increased and many students were concerned virtually the leadership of the UMAS and Chicano movements on the CU Boulder Campus. On May 27, 1974, Reyes Martinez, an attorney from Alamosa, Colorado, Martinez's girlfriend, Una Jaakola, CU Boulder alumna University of Colorado Boulder, and Neva Romero, an UMAS pupil attention CU Boulder, were killed in a car bombing at Bedrock'southward Chautauqua Park.[l] [51] Ii days later another machine bomb exploded in the Burger Rex parking lot at 1728 28th St. in Boulder, killing Francisco Dougherty, 20, Florencio Grenado, 31, and Heriberto Teran, 24, and seriously injuring Antonio Alcantar. Information technology was after determined both explosions were caused by homemade bombs composed of up to nine dynamite sticks.[52] Nearly of the victims were involved in the UMAS movement in Boulder, Colorado.[53] They came to be known as Los Seis de Boulder. Many students in the UMAS and Chicano motion believed the bombing was directly correlated to the students' demands and rise attention on the Chicano movement.[49] An arrest was never made in connexion with the auto bombing.[53]

A University of Colorado Boulder Main of Fine Arts pupil, Jasmine Baetz, created an fine art exhibit in 2019 defended to Los Seis de Bedrock. The art exhibit is a seven-pes-tall rectangular sculpture that includes six mosaic tile portraits. The depiction of each activist faces the direction in which he or she died. It currently sits in front of the TB-1 edifice east of Macky Auditorium on the CU-Boulder campus. Baetz, a Canadian, had by chance seen the film Symbols of Resistance, a documentary about Los Seis de Boulder, in 2017. She became inspired to create a piece of art to honour the activists. She invited customs participation in the project; over 200 people worked on information technology in some capacity. The base of the sculpture states, "Defended in 2019 to Los Seis de Boulder & Chicana and Chicano students who occupied TB-1 in 1974 & everyone who fights for equity in pedagogy at CU Boulder & the original stewards of this land who were forcibly removed & all who remain." Information technology besides states, "Por Todxs Quienes Luchan Por La Justicia" (for all those who fight for justice).[54] [55] CU students take protested a campus decision not to make the art exhibit permanent.[56] CU announced the exhibit would be fabricated permanent in September 2020.[57]

A memorial in honor of Los Seis de Boulder was installed at Chautauqua Park in Boulder on May 27, 2020, at the location of the showtime car bomb explosion exactly 46 years ago. The Urban center of Boulder provided a $5000 grant for the memorial which the Colorado Chautauqua Association's Buildings and Grounds Commission and the Urban center of Boulder Landmarks Review Commission approved. Family members of the deceased gathered to watch as the stone monument was put in place.[58]

Anti-war activism [edit]

The Chicano Moratorium was a movement past Chicano activists that organized anti-Vietnam War demonstrations and activities throughout the Southwest and other Mexican American communities from Nov 1969 through August 1971. The motion focused on the unduly high decease rate of Mexican American soldiers in Vietnam as well as the discrimination faced at home.[59] Afterwards months of demonstrations and conferences, it was decided to hold a National Chicano Moratorium demonstration against the war on Baronial 29, 1970. The march began at Dais Park in LA and headed towards Laguna Park (since renamed Ruben F. Salazar Park) alongside 20,000 to 30,000 people. The Committee members included Rosalio Muñoz and Corky Gonzales and only lasted one more year, merely the political momentum generated by the Moratorium led many of its activists to continue their activism in other groups.[60] The rally became violent when there was a disturbance in Laguna Park. There were people of all ages at the rally considering information technology was intended to be a peaceful event. The sheriffs who were there later claimed that they were responding to an incident at a nearby liquor store that involved Chicanos who had allegedly stolen some drinks.[61] The sheriffs likewise added that upon their arrival they were hit with cans and stones. Once the sheriff arrived, they claimed the rally to be an "unlawful associates" which turned trigger-happy. Tear gas and mace were everywhere, demonstrators were hitting by billy clubs and arrested equally well. The event that took place was being referred to equally a riot, some have gone as far to call it a "Police Anarchism" to emphasize that the law were the ones who initiated information technology[61]

Relations with Police [edit]

Police subduing Chicano Movement rioters in San Jose, California.

Edward J. Escobar details in his work the human relationship between diverse movements and demonstrations within the Chicano Movement and the Los Angeles Police Department between the years 1968–1971. His chief argument explores how "police violence, rather than subduing Chicano movement activism, propelled that activism to a new level -- a level that created a greater police problem than had originally existed".[22] : 1486 At one Chicano Moratorium (likewise referred to every bit the National Chicano Moratorium) demonstration every bit part of the Anti-state of war activism, popular journalist Ruben Salazar was killed by law after they shot a tear-gas projectile into the Argent Dollar Café where he was later covering the moratorium demonstration and succeeding riots.[22] This is an instance Escobar presents that inspired political consciousness in an even broader base of Mexican-Americans, many considering him a "martyr".[22] : 1485

Relations between Chicano activists and the police mirrored those with other movements during this time. As Escobar states, Blackness Civil Rights activists in the 50s and 60s "ready the stage past focusing public attending on the issue of racial discrimination and legitimizing public protestation every bit a manner to gainsay discrimination."[22] : 1486 Marginalized communities began using this public platform to speak against injustices they had been experiencing for centuries at the hands of the U.South. authorities, perpetuated by police force departments and other institutions of power. Like many of the movements during this time, Chicanos took inspiration from the Black Panther Party and used their race, historically manipulated to disenfranchise them, as a source of cultural nationalism and pride.

Edward J. Escobar claims the Chicano Movement and its sub-organizations were infiltrated by local law enforcement and the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) to learn information and cause destabilization from within the organizations. Methods used by law enforcement included "red-baiting, harassment and arrest of activists, infiltration and disruption of movement organizations, and violence."[22] : 1487 Agent provocateurs were often planted in these organizations to disrupt and destabilize the movements from inside. Repression from law enforcement broadened Chicano political consciousness, their identities in relation to the larger social club, and encouraged them to focus their efforts in politics.

Chicano fine art [edit]

"Delight, Don't Bury Me Alive!"

Art of the Motility was the burgeoning of Chicano art fueled by heightened political activism and energized cultural pride. Chicano visual art, music, literature, dance, theater and other forms of expression take flourished. During the 20th century, an emergence of Chicano expression developed into a full-scale Chicano Art Motility. Chicanos adult a wealth of cultural expression through such media as painting, drawing, sculpture and printmaking. Similarly, novels, poetry, brusk stories, essays and plays accept flowed from the pens of contemporary Chicano writers.

Operating inside the Chicano art motility is the concept "rasquachismo," which comes from the Spanish term "rasquache."[62] This term is used to describe something that is of lower quality or condition and is often correlated with groups in a club that fit this description and accept to get resourceful to get past.[62] Chicano artists being resourceful can be seen when artists cutting upwardly can cans and flatten them out into rectangles to use as canvases.[62] In addition to its influence in the visual arts, the concept "rasquachismo" informs Chicano performing arts.[62] El Teatro Campesino's La Carpa de los Rasquachis is a play written by Luis Valdez in 1972, which tells the story of a farmworker that has migrated to the United States from Mexico; this play teaches the audience to expect for means to be resourceful.[62]

Chicano Art developed effectually the 1960s during the Chicano Liberation Movement.[13] [63] In its start stages, Chicano art was distinguished by the expression through public art forms. Many artists saw the need for self-representation because the media was trying to suppress their voices.[xiii] Chicano artists during this time used visual arts, such as posters and murals in the streets, as a class of communication to spread the give-and-take of political events affecting Chicano civilisation; UFW strikes, student walkouts, and anti-war rallies were a few of the main topics depicted in such art.[xiii] Artists similar Andrew Zermeño reused certain symbols recognizable from Mexican culture, such as skeletons and the Virgen de Guadalupe, in their ain fine art to create a sense of solidarity between other oppressed groups in the United States and globally.[xiii] In 1972, the group ASCO, founded by Gronk, Willie Herrón, and Patssi Valdez, created conceptual art forms to appoint in Chicano social protests; the group utilized the streets of California to display their bodies every bit murals to draw attending from dissimilar audiences.[13]

Chicano artists created a bi-cultural way that included United states of america and Mexican influences. The Mexican style can exist found by their use of vivid colors and expressionism. The art has a very powerful regionalist factor that influences its work. Examples of Chicano muralism can be plant in California at the celebrated Estrada Courts Housing Projects in Boyle Heights.[64] Another example is La Marcha Por La Humanidad, which is housed at the University of Houston.

Chicano performing arts also began developing in the 1960s with the creation of bilingual Chicano theater, playwriting, comedy, and trip the light fantastic.[65] Recreating Mexican performances and staying in line with the "rasquachismo" concept, Chicanos performed skits about inequalities faced by people within their culture on the back of trucks.[65] The group ASCO also participated in the performing art course by having "guerrilla" performances in the streets.[65] This fine art form spread to the spoken discussion in 1992 when a collection of Chicana spoken give-and-take was recorded on compact disc.[65] Chicano comedians accept as well been publicly known since the 1980s, and in 1995, the outset televised Chicano comedy series was produced by Culture Clash.[65]

About 20 years later on the Chicano Motion, Chicano artists were affected by political priorities and societal values, and they were likewise becoming more accepted past society. They were becoming more interested making pieces for the museums and such, which acquired Chicano art to go more commercialized, and less concerned with political protestation.[66]

Chicano art has connected to expand and adapt since the Chicano Movement.[66] Today the Millennial Chicano generation has begun to redefine the Chicano art space with modernized forms of self-expression, although some artists still endeavor to preserve the traditional Chicano fine art forms.[66] Equally the community of Chicano artists expands and diversifies, Chicano fine art can no longer fit nether merely one aesthetic.[66] The younger generation takes advantage of engineering science to create art and draws inspiration from other cultural art forms, such every bit Japanese anime and hip hop.[66] Chicano art is now defined by the experimentation of self-expression, rather than producing fine art for social protests.[66]

Chicano press [edit]

The Chicano press was an of import component of the Chicano Movement to disseminate Chicano history, literature, and electric current news.[67] The printing created a link between the core and the periphery to create a national Chicano identity and community. The Chicano Press Clan (CPA) created in 1969 was significant to the development of this national ethos. The CPA argued that an active press was foundational to the liberation of Chicano people, and represented about xx newspapers, generally in California but also throughout the Southwest.

Chicanos at many colleges campuses too created their ain student newspapers, but many ceased publication within a year or two, or merged with other larger publications. Organizations such equally the Brown Berets and MECHA also established their ain independent newspapers. Chicano communities published newspapers like El Grito del Norte from Denver and Caracol from San Antonio, Texas.

Over 300 newspapers and periodicals in both large and pocket-sized communities have been linked to the Movement.[68]

Chicano Organized religion [edit]

Many in the Chicano Movement were influenced past their Catholic identities. The most famous activist who heavily relied on Catholic influence and practices was Cesar Chávez. Fasting was mutual by many activists though who would only pause their fasts to consume communion.[69] The Virgin of Guadalupe was likewise used as a symbol of inspiration during many protests.[70] The Chicano Movement was frequently inspired by their religious convictions to go along the tradition of commitment to social change and asserting their rights. There was too influence from ethnic forms of religion combined with Cosmic beliefs. Altars would exist fix past the matriarchs of families that often included both Cosmic symbols and indigenous religious symbols.[71] Both Catholic beliefs and the inclusion of ethnic religious practices were influenced many in the Chicano Movement to continue their protests and fight to equality.[72]

Aztlán [edit]

An commodity virtually what a wedlock in Aztlán would take been like.

The concept of Aztlán as the place of origin of the pre-Columbian Mexican civilisation became a symbol for various Mexican nationalist and indigenous movements.

The proper name Aztlán was kickoff taken upwardly by a group of Chicano independence activists led by Oscar Zeta Acosta during the Chicano movement of the 1960s and 1970s. They used the proper noun "Aztlán" to refer to the lands of Northern Mexico that were annexed past the United States as a result of the Mexican–American War. Combined with the claim of some historical linguists and anthropologists that the original homeland of the Aztecan peoples was located in the southwestern United States even though these lands were historically the homeland of many American Indian tribes (eastward.1000. Navajo, Hopi, Apache, Comanche, Shoshone, Mojave, Zuni and many others). Aztlán in this sense became a "symbol" for mestizo activists who believed they take a legal and primordial right to the land, although this is disputed by many of the American Indian tribes currently living on the lands they claim as their historical homeland. Some scholars debate that Aztlan was located inside Mexico proper. Groups who have used the name "Aztlán" in this mode include Plan Espiritual de Aztlán, MEChA (Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlán, "Chicano Pupil Movement of Aztlán").

Many in the Chicano Movement attribute poet Alurista for popularizing the term Aztlán in a verse form presented during the Chicano Youth Liberation Conference in Denver, Colorado, March 1969.[73]

See also [edit]

- Adela Sloss Vento

- Chicano

- Chicanismo

- Chicano nationalism

- Chicano studies

- Chicano/a Movement in Washington State History Projection

- El Chicano

- Mario Cantu

- Mestizos in the United States

References [edit]

- ^ Mazón, Mauricio (1989). The Zoot-Adapt Riots: The Psychology of Symbolic Anything. University of Texas Press. pp. 118. ISBN9780292798038.

- ^ López, Miguel R. (2000). Chicano Timespace: The Poetry and Politics of Ricardo Sánchez. Texas A&M Academy Press. pp. 113. ISBN9780890969625.

- ^ Francisco Jackson, Carlos (2009). Chicana and Chicano Art: ProtestArte. University of Arizona Press. p. 135. ISBN9780816526475.

- ^ Kelley, Robin (1996). Race Rebels: Culture, Politics, And The Black Working Grade. Gratis Printing. p. 172. ISBN9781439105047.

- ^ a b c Mantler, Gordon K. (2013). Power to the Poor: Black-Brown Coalition and the Fight for Economical Justice, 1960-1974. University of North Carolina Printing. pp. 65–89. ISBN9781469608068.

- ^ a b Martinez HoSang, Daniel (2013). "Changing Valence of White Racial Innocence". Blackness and Brown in Los Angeles: Across Disharmonize and Coalition. University of California Press. pp. 120–23.

- ^ Rodriguez, Marc Simon (2014). Rethinking the Chicano Movement. Taylor & Francis. p. 64. ISBN9781136175374.

- ^ a b Rosales, F. Arturo (1996). Chicano! The History of the Mexican American Civil Rights Movement. Arte Publico Press. pp. xvi. ISBN9781611920949.

- ^ Macías, Anthony (2008). Mexican American Mojo: Popular Music, Dance, and Urban Civilization in Los Angeles, 1935–1968 . Duke University Press. pp. ix. ISBN9780822389385.

- ^ San Miguel, Guadalupe (2005). Brown, Not White: School Integration and the Chicano Motility in Houston. Texas A&Yard University Press. p. 200. ISBN9781585444939.

- ^ Mora, Carlos (2007). Latinos in the West: The Student Motion and Academic Labor in Los Angeles. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 53–sixty. ISBN9780742547841.

- ^ Mora-Ninci, Carlos (1999). The Chicano/a Educatee Motion in Southern California in the 1990s. Academy of California, Los Angeles. p. 358.

- ^ a b c d e f Gudis, Catherine (2013-11-15), "I Idea California Would Be Different: Defining California through Visual Culture", A Companion to California History, Oxford, Britain: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, pp. 40–74, retrieved 2021-12-15

- ^ Kunkin, Fine art (1972). "Chicano Leader Tells of Starting Violence to Justify Arrests". The Chicano Movement: A Historical Exploration of Literature. Los Angeles Complimentary Press. pp. 108–110. ISBN9781610697088.

- ^ Montoya, Maceo (2016). Chicano Movement for Beginners . For Beginners. pp. 192–93. ISBN9781939994646.

- ^ Delgado, Héctor Fifty. (2008). Encyclopedia of Race, Ethnicity, and Society. SAGE Publications. p. 274. ISBN9781412926942.

- ^ Suderburg, Erika (2000). Infinite, Site, Intervention: Situating Installation Fine art. University of Minnesota Press. p. 191. ISBN9780816631599.

- ^ Gutiérrez-Jones, Carl (1995). Rethinking the Borderlands: Betwixt Chicano Culture and Legal Discourse. University of California Press. p. 134. ISBN9780520085794.

- ^ Orosco, José-Antonio (2008). Cesar Chavez and the Common Sense of Nonviolence. University of New Mexico Printing. pp. 71–72, 85. ISBN9780826343758.

- ^ Saldívar-Hull, Sonia (2000). Feminism on the Border: Chicana Gender Politics and Literature. University of California Press. pp. 29–34. ISBN9780520207332.

- ^ Rhea, Joseph Tilden (1997). Race Pride and the American Identity . Harvard University Press. pp. 77–78. ISBN9780674005761.

- ^ a b c d e f Escobar, Edward J. (March 1993). "The Dialectics of Repression: The Los Angeles Police Department and the Chicano Movement, 1968-1971". The Journal of American History. 79 (4): 1483–1514. doi:10.2307/2080213. JSTOR 2080213.

- ^ "LULAC: LULAC History - All for One and One for All". Archived from the original on fifteen October 2015. Retrieved 23 September 2015.

- ^ "Constitute in the Garcia Athenaeum: Inspiration from a Notable Civil Rights Leader". HistoryAssociates.com. May 2013. Archived from the original on iii Feb 2018. Retrieved 31 January 2018.

- ^ Williams, Rudi. "Congress Lauds American G.I. Forum Founder Garcia". U.S. Department of Defence. Archived from the original on 2012-04-14.

- ^ "American GI Forum Map". Mapping American Social Movements. Archived from the original on 2016-12-19. Retrieved 2017-01-27 .

- ^ "LatinoLA - Hollywood :: Mendez v. Westminster". LatinoLA. Archived from the original on eleven September 2015. Retrieved 23 September 2015.

- ^ "HERNANDEZ v. TEXAS. The Oyez Projection at IIT Chicago-Kent College of Police". Oyez.org. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 9 Apr 2018.

- ^ MALDEF - About Us Archived April 22, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Stern, A. One thousand. (2005). "STERILIZED in the Name of Public Health". American Journal of Public Wellness. 95 (7): 1128–1138. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2004.041608. PMC1449330. PMID 15983269.

- ^ "Untitled Document". Archived from the original on four March 2016. Retrieved 23 September 2015.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-03-06. Retrieved 2013-02-01 .

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived re-create as title (link) - ^ "Chicano Power in the UsA." Archived 2012-04-25 at the Wayback Machine - Xcano Media, Los Angeles

- ^ Ordóñez, Elizabeth (Summertime 2006). "Sexual Politics and the Theme of Sexuality in Chicana Poetry". Letras Femeninas. 32: 67–92.

- ^ a b c d due east Hurtado, Aída (1998). "Sitios y Lenguas: Chicanas Theorize Feminisms". Hypatia. thirteen (2): 134–161. doi:ten.1111/j.1527-2001.1998.tb01230.x. JSTOR 3810642.

- ^ "The Nascence of Chicana Feminist Thought". umich.edu. Archived from the original on 2019-05-24. Retrieved 2019-06-02 .

- ^ Mariscal, Jorge (2002). "Left turns in the Chicano Movement: 1965-1975". Monthly Review. 54 (3): 59–68. doi:10.14452/mr-054-03-2002-07_6. ProQuest 213134584.

- ^ "Chicano/Latino Movements History and Geography". Mapping American Social Movements Through the 20th Century. Archived from the original on 2017-02-02.

- ^ ""Our First Poll Revenue enhancement Drive": The American G.I. Forum Fights Disenfranchisement of Mexican Americans in Texas". Archived from the original on 24 Feb 2015. Retrieved 23 September 2015.

- ^ "Election of Roybal, democracy at work : extension of remarks of Hon. Chet Holifield of California in the House of Representatives". Retrieved 23 September 2015.

- ^ "Untitled Document". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 23 September 2015.

- ^ Ensslin, John C. (1999-09-21). "Chicano movement was a turning point for Denver". Archived from the original on 2009-06-27.

- ^ Ayyoub, Loureen (2020-08-29). "Chicano Moratorium Recognizes 50 Year Anniversary in East LA". SPECTRUM NEWS. Charter Communications.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "The Chicano Student Walkout". laep.org. May 1998. Archived from the original on 2003-05-17.

- ^ "The South Texan Texas A&M University-Kingsville" (PDF). Tamuk.edu. March 23, 2010. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 9 April 2018.

- ^ a b Moore, J. W., & Cuéllar, A. B. (1970). Mexican Americans. Ethnic groups in American life serial. Englewood, Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall. p. 150. ISBN 0-13-579490-0

- ^ "MEChA chapters map". Mapping American Social Movements. Archived from the original on 2017-01-ten. Retrieved 2017-01-27 .

- ^ Moore, J. West., & Cuéllar, A. B. (1970). Mexican Americans. Ethnic groups in American life series. Englewood, Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall. p. 151. ISBN 0-13-579490-0

- ^ a b c "Diario de la Gente, El May 5, 1973 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org . Retrieved 2019-06-29 .

- ^ "Diario de la Gente, El June 11, 1974 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Drove". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org . Retrieved 2019-06-29 .

- ^ "Bedrock bombings remembered in talks, documentary". Boulder Daily Camera. 2014-05-22. Retrieved 2019-08-09 .

- ^ Dodge, Jefferson; Dyer, Joel (2014-05-29). "Los Seis de Boulder". Boulder Weekly. Archived from the original on 2019-03-24. Retrieved 2019-08-09 .

- ^ a b "Filmmaker seeks answers in 1974 Boulder car bombings". Boulder Daily Camera. 2017-09-eighteen. Retrieved 2019-06-29 .

- ^ "CU Boulder MFA student creates sculpture to remember Los Seis de Boulder". Boulder Daily Camera. 2019-08-26. Retrieved 2019-09-04 .

- ^ Dyer, Joel (2019-08-29). "The perils of forgotten history". Boulder Weekly. Archived from the original on 2019-09-04. Retrieved 2019-09-04 .

- ^ "Students demand "Los Seis" statue exist fabricated permanent". Bedrock Daily Camera. 2020-03-12. Retrieved 2020-03-12 .

- ^ "Los Seis sculpture to remain at CU Boulder". Boulder Daily Camera. 2020-09-17. Retrieved 2020-09-17 .

- ^ "New memorial of Los Seis de Boulder installed at Chautauqua". Boulder Daily Photographic camera. 2020-05-28. Retrieved 2020-06-01 .

- ^ "30 Years Later on the Chicano Moratorium". Frontlines of Revolutionary Struggle. 26 March 2010. Archived from the original on 26 September 2015. Retrieved 23 September 2015.

- ^ "Archived re-create". Archived from the original on 2011-05-15. Retrieved 2013-09-xv .

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ a b T., García, Mario (2015-05-12). The Chicano generation: testimonies of the motion. Oakland, California. ISBN9780520286023. OCLC 904133300.

- ^ a b c d e Gutiérrez, Laura G. "Rasquachismo." Keywords for Latina/o Studies, Deborah R. Vargas, et al., New York University Printing, 1st edition, 2017. Ideology Reference. Accessed 22 Nov. 2021.

- ^ Goldman, Shifra Thousand. "Latin American artists of the USA". Oxford Fine art Online. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- ^ "Estrada Courts". Laconservancy.org. Archived from the original on 10 Apr 2018. Retrieved 9 April 2018.

- ^ a b c d e Habell-Pallán, Michelle. "Chicano Performing and Graphic Arts." Encyclopedia of American Studies, edited by Simon Bronner, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1st edition, 2018. Credo Reference. Accessed 22 Nov. 2021.

- ^ a b c d due east f Ybarra-Frausto, Tomás. "Post-Movimiento: The Gimmicky (Re)Generation of Chicana/o Art." Blackwell Companions in Cultural Studies: A Companion to Latina/o Studies, Juan Flores, and Renato Rosaldo, Wiley, 1st edition, 2011. Credo Reference. Accessed 22 Nov. 2021.

- ^ "Chicano/Latino Movements History and Geography". Mapping American Social Movements. Archived from the original on 2017-02-02.

- ^ "Chicano Newspapers and Periodicals, 1966-1979". Mapping American Social Movements. Archived from the original on 2017-01-03.

- ^ Espinosa, Gastón (2005). Latino Religions And Borough Activism in the United states of america. New York: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Kurtz, Donald V. (1982). "The Virgin of Guadalupe and the Politics of Becoming Human". Journal of Anthropological Research. 38 (2): 194–210. doi:10.1086/jar.38.2.3629597. ISSN 0091-7710. JSTOR 3629597. S2CID 147394238.

- ^ García, Alma (1997). Chicana Feminist Idea. New York: Routledge.

- ^ Lara, Irene (2005). "BRUJA POSITIONALITIES: Toward a Chicana/Latina Spiritual Activism". Chicana/Latina Studies. 4 (2): ten–45. ISSN 1550-2546. JSTOR 23014464.

- ^ "Alurista Essay - Critical Essays". eNotes. Archived from the original on 27 May 2011. Retrieved 23 September 2015.

Further reading [edit]

- Gómez-Quiñones, Juan, and Irene Vásquez. Making Aztlán: Ideology and Culture of the Chicana and Chicano Movement, 1966-1977 (2014)

- Meier, Matt S., and Margo Gutiérrez. Encyclopedia of the Mexican American civil rights move (Greenwood 2000) online

- Orozco, Cynthia Eastward. No Mexicans, women, or dogs allowed: The ascension of the Mexican American civil rights movement (University of Texas Printing, 2010) online

- Rosales, F. Arturo. Chicano! The history of the Mexican American civil rights motility (Arte Público Press, 1997); online

- Sánchez, George I (2006). "Ideology, and Whiteness in the Making of the Mexican American Ceremonious Rights Move, 1930–1960". Journal of Southern History. 72 (iii): 569–604. doi:10.2307/27649149. JSTOR 27649149.

External links [edit]

- "La Batalla Está Aquí": The Chicana/o Movement in Los Angeles, interview series, Centre for Oral History Research, UCLA Library Special Collections, Academy of California, Los Angeles.

- Mexican-American.org – Network of the Mexican American Community

- NetworkAztlan.com - Network Aztlan

- Chicana community search folio

- Chicano Newspapers and Periodicals 1969-1979 A map of Chicano press across the country from 1969 to 1970 based on serial listings collected by the University of California Libraries.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chicano_Movement

0 Response to "what factors led to the rise of the american indian movement in the 1960s?"

Post a Comment